Toronto Star

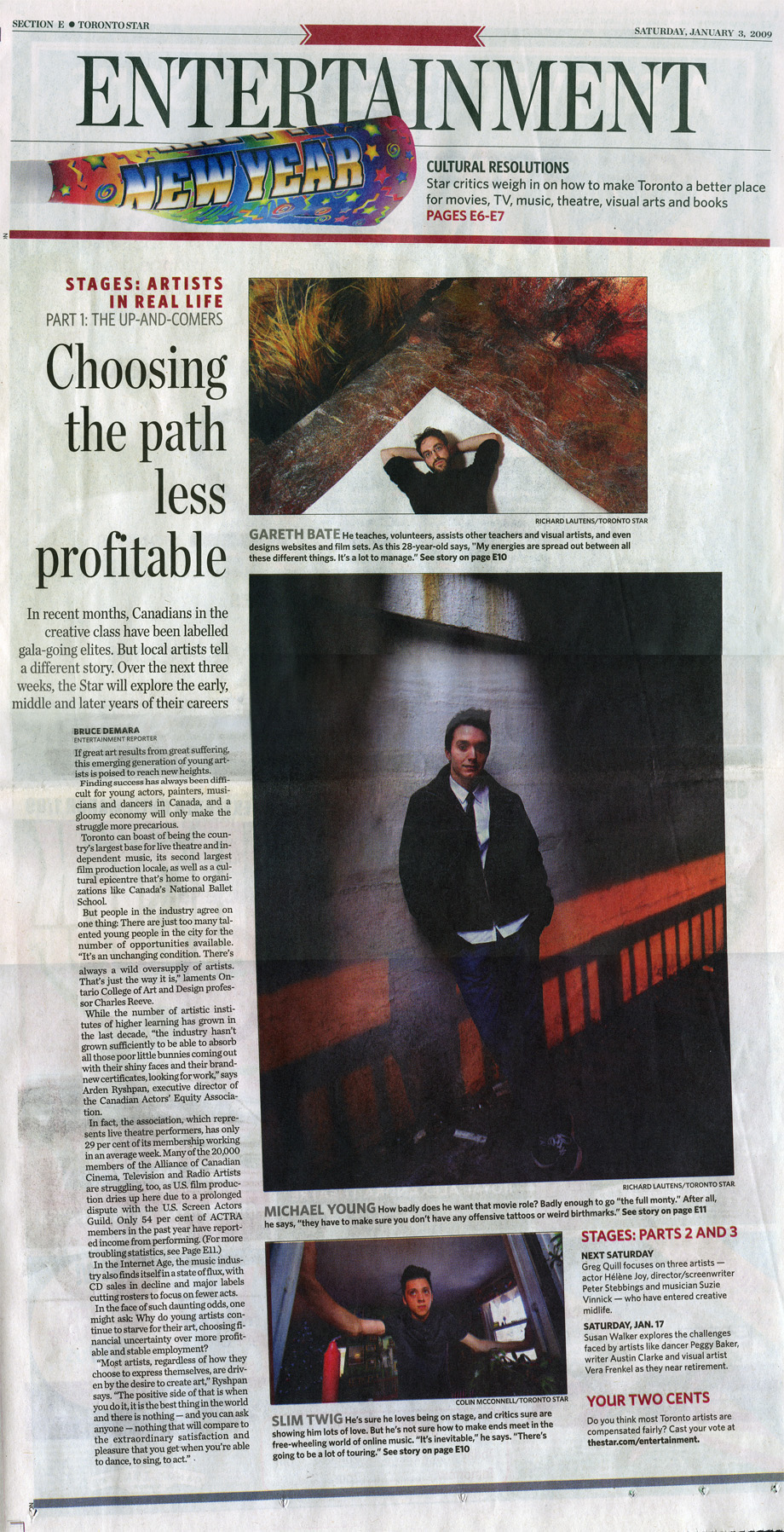

"Gareth Bate Caught Between a Job and a Cold Place."

(Entertainment Cover Story: Stages: Artists In Real Life: The Up and Comers)

Bruce Demara,

Saturday, Jan.3 2009.

Photographer: Richard Lautens

Curtesy of the Toronto Star

Return to Press Menu | Read as Plain Text |

View Website Source

Toronto Star

"Gareth Bate Caught Between a Job and a Cold Place."

(Entertainment Cover Story: Stages: Artists In Real Life: The Up and Comers)

Bruce Demara,

Saturday, Jan.3 2009.

Photographer: Richard Lautens

Curtesy of the Toronto Star

Return to Press Menu | View Website Source

In his short career as a visual artist, Gareth Bate has literally had his ups and downs.

After winning a coveted prize giving him year-long use of prime studio space, Bate has since moved from a roomy, light-filled top floor to a much smaller studio – shared with a fellow artist – in the basement of 401 Richmond St. W.

"It was about 500 square feet, it was really spectacular and it had these huge windows," Bate says wistfully of his former space. The new studio, while adequate, is damp and gets quite cold in winter.

"I normally keep the windows open because it gets musty," he says, half-apologetically.

But Bate, 28, is anything but downcast. At $230 a month, the space is a steal, and is large enough for him to continue his career as an artist after graduating last year from the Ontario College of Art and Design and winning the 401 Richmond Career-Launcher Prize.

The building, owned by philanthropist Margaret Zeidler, is a former factory converted into an artists' colony. "This whole building is filled with galleries and architects and magazines and charities and film festivals, all kinds of people who need some help in having affordable rates," Bate says.

In other words, people like him.

But becoming a successful visual artist in Canada – even in its creative hub, Toronto – is not a job for the easily discouraged.

Charles Reeve, a professor at OCAD, says that while Toronto has "matured" as a city, with a growing number of private galleries and patrons, most artists find it hard to earn a living here. "There simply is not enough room to give shows to everybody who wants and deserves a show. ... It's really important to be aware of the fact ... that a lot of people who really have the goods never make it. They never get the lucky break," he says.

Bate sees his vocation as "a life decision, because you're dedicating yourself to something that is not necessarily going to bring you lots of money, but hopefully will be spiritually enlightening."

Originally from South Africa, Bate arrived in Canada with his mother at age 6. From early on, he loved to draw and paint. He grew up in Oakville, earning a high school art award for his dramatic murals before attending a program for adults run by the Toronto District School Board at Central Technical School. From there, he went on to OCAD.

Post-graduation, Bate's creativity flowed easily (and prolifically) during his year on the top floor. But it's a little harder now, in part because of a hectic schedule that includes holding down several jobs.

Bate teaches art part-time at Central Tech, has a teaching assistant job at OCAD, is a freelance web designer and is also a studio assistant to Roger Wood, one of the few artists Bate knows who makes a living from his craft, with his funky reconstructed clocks.

Bate recently completed a one-off set design job in Montreal. He also runs Central Tech's alumni network on a volunteer basis, and maintains his own website. Any time remaining is devoted to painting, as well as photography, video and occasionally performance art.

"For me, it's important to work in a variety of different (media)," says Bate. "Painting can't say everything." But he acknowledges, "My energies are spread out between all these different things. It's a lot to manage."

And it's not likely to get easier. Despite positive reviews – and sales – from shows he mounted in recent months, Bate has a monumental decision ahead: pursue a master's degree, which would allow him to teach art at the university level, thus earning a good living while continuing to make art, or continue to struggle as a full-time artist.

With an annual income under $20,000, Bate is also still paying off a student loan of about $15,000. So incurring further debt is a daunting investment in his future.

"It's a problem I'm just kind of avoiding at the moment. It's not like I'm a doctor and I'm going to go and make the money back. That's the problem – the prospect of making tons of money is not there. It's going to take a while to pay back," Bate says. "I know very few artists who earn a living entirely from their art work. It's a little discouraging but it's just the reality of it."

While he would rather be working on art full-time, sketching at High Park's Grenadier Pond or spending a summer month on Prince Edward Island, Bate has few regrets.

"(Art) brings out lots of scary stuff you didn't know you had. But I find through my work I'm learning who I am. From making art, I'm closer to a sense of myself," he says. "I don't feel pessimistic. I feel more pessimistic about the rest of the world than I do about art."

Artists choose the path less profitable

If great art results from great suffering, this emerging generation of young artists is poised to reach new heights.

Finding success has always been difficult for young actors, painters, musicians and dancers in Canada, and a gloomy economy will only make the struggle more precarious.

Toronto can boast of being the country's largest base for live theatre and independent music, its second largest film production locale, as well as a cultural epicentre that's home to organizations like Canada's National Ballet School.

But people in the industry agree on one thing: There are just too many talented young people in the city for the number of opportunities available. "It's an unchanging condition. There's always a wild oversupply of artists. That's just the way it is," laments Ontario College of Art and Design professor Charles Reeve.

While the number of artistic institutes of higher learning has grown in the last decade, "the industry hasn't grown sufficiently to be able to absorb all those poor little bunnies coming out with their shiny faces and their brand-new certificates, looking for work," says Arden Ryshpan, executive director of the Canadian Actors' Equity Association.

In fact, the association, which represents live theatre performers, has only 29 per cent of its membership working in an average week. Many of the 20,000 members of the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists are struggling, too, as U.S. film production dries up here due to a prolonged dispute with the U.S. Screen Actors Guild. Only 54 per cent of ACTRA members in the past year have reported income from performing. (For more troubling statistics, see Page E11.)

In the Internet Age, the music industry also finds itself in a state of flux, with CD sales in decline and major labels cutting rosters to focus on fewer acts.

In the face of such daunting odds, one might ask: Why do young artists continue to starve for their art, choosing financial uncertainty over more profitable and stable employment?

"Most artists, regardless of how they choose to express themselves, are driven by the desire to create art," Ryshpan says. "The positive side of that is when you do it, it is the best thing in the world and there is nothing – and you can ask anyone – nothing that will compare to the extraordinary satisfaction and pleasure that you get when you're able to dance, to sing, to act."